The fate of the Iran nuclear agreement will be in

question once President-elect Donald Trump, who has offered

contradictory positions on the deal, enters the White

House.

The future commander in chief, who has said he likes to be

unpredictable, has variously promised to scrap the agreement

entirely, renegotiate a better deal more favorable to the U.S. and

vigorously enforce the current agreement. Sometimes he vows to

enact two opposing policies in the same speech.

It’s anyone’s guess what Trump will actually do once his term

starts, but there’s reason to believe he won’t immediately sabotage

the nuclear accord. During the Republican primary race, most of

Trump’s opponents said they’d tear up the deal on their first day

in office. Trump, at one point, gave a slightly more nuanced

approach, acknowledging the limited effect sanctions against Iran

would have without buy-in from international partners.

"I know it would be very popular for me to do what a couple of

‘em said — ‘we’re gonna rip it up,’" Trump said in September of

last year. "Iran is going to be an absolute terror, and it’s

horrible that we have to live with it. Nevertheless, we have a

contract. We’ve lost the power of sanctions because all of these

other folks, all of these other countries that were with us, are

gone now."

Even when Trump takes a more hawkish tone on it, the nuclear

deal doesn’t appear to be one of his top priorities. He speaks more

often, for example, of repairing ties with Russia, one of the seven

countries involved in negotiating the landmark agreement. But

former State Department officials who worked on the nuclear accord

worry that the fragile deal is at risk of collapsing under Trump

even if he doesn’t actively pull out of it. Keeping it intact, they

say, will take proactive effort from the next administration.

The sanctions relief provided to Iran as part of the deal needs

to be renewed every 120 to 180 days, which means Trump will need to

actively enforce the agreement within his first few months in

office, wrote Richard Nephew in a paper published by the Columbia

Center for Global Energy Policy. It’s possible, said Nephew, who

coordinated Iran sanctions policy when he was at the State

Department, that Trump would withhold sanctions relief and use the

leverage as part of his push to renegotiate the deal. That could be

a nonstarter in Iran, where President Hassan Rouhani is up for

re-election next year.

There are other, less tangible, steps that the Obama

administration has taken to keep the nuclear agreement alive over

the past year and a half. Cognizant of the fact that the deal will

only work if Iran feels economic relief, Secretary of State John

Kerry has publicly assured European companies that it is safe to do

business with Iran even while U.S. sanctions remain in place.

Tehran already feels that the U.S. should be doing more to reassure

European businesses ― and it’s hard to imagine former Speaker of

the House Newt Gingrich Newt Gingrich, reportedly a contender to be

Trump’s secretary of state, taking steps to encourage investment in

Iran.

"If it’s just left to relatively powerless bureaucrats with no

support from the top to make tough decisions on how to encourage

trade with Iran and makes sure it gets the economic benefits the

U.S. committed to, then over time the deal will die," predicted

Ilan Goldenberg, a former Iran adviser at the Pentagon.

A Trump administration is also less likely to block the

Republican-controlled Congress from passing legislation that could

undermine the nuclear deal and prompt Iran to walk away. Ever since

the Republicans failed to kill the agreement last year, lawmakers

have been floating additional sanctions against Iran, arguing that

the deal gives the U.S. the right to punish Iran for non-nuclear

issues.

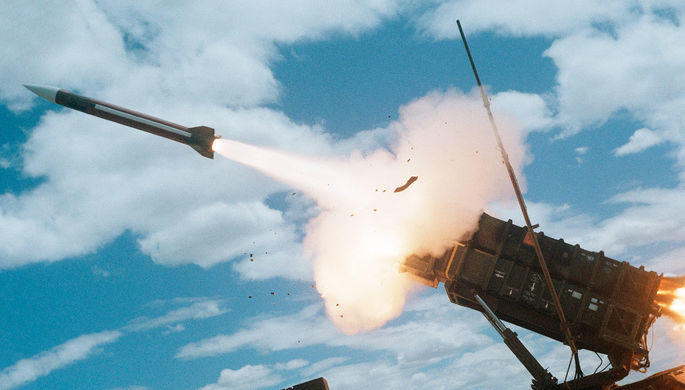

While the Obama administration has used its executive authority

earlier this year to enact new sanctions related to Iran’s

ballistic missile program, it has also leaned heavily on

Congressional Democrats to block sanctions that could be perceived

as violating the intent of the nuclear agreement. The combination

of a Trump administration and incoming Senate Minority Leader Chuck

Schumer (D-N.Y.), who voted against the nuclear accord, means it

would be easier for Republicans to weaken or kill the agreement

through new legislation. (Since the agreement has gone into effect,

Schumer hasn’t attempted to undermine it and has no plans to do so,

a Senate Democratic aide said.)

The most worrisome scenario, former government officials say, is

how Trump would react if he believes Iran violates the deal. "It’s

a question of what happens next time the Iranians mess around on

the margins or do something like inadvertently (or on purpose) have

too much [low enriched uranium] in stock," Goldenberg wrote in an

email. So far, minor disputes like these have been resolved by an

international board established for that purpose, he said. Will a

Trump administration continue to do so, he wondered, "or will it

quickly escalate to an international crisis?"