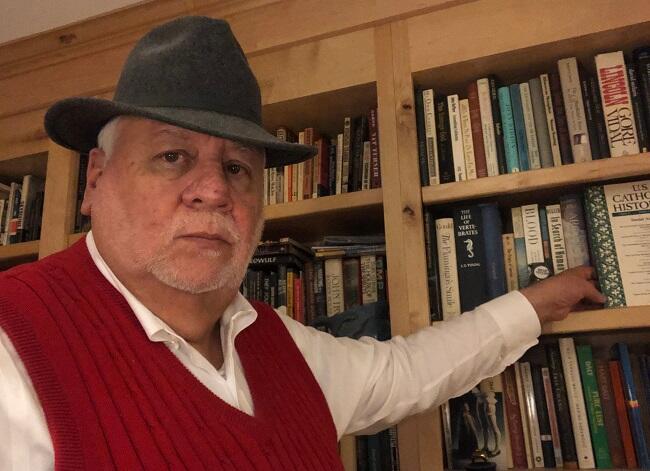

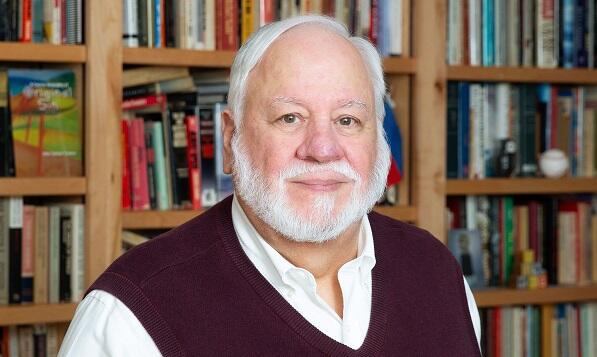

Axar.az presents the article "Cri De Cœur " by John Samuel Tieman.

Last night on the news, I watched as Ukrainian parents held their wounded baby. The child died in their arms. This week, I'm not writing a column. This week, I'm writing a scream.

I don’t understand how anyone can romanticize war. On TV, you know a guy is OK when he says, “Ah, it's just a leg wound, sarge. I'm fine.” The brave words are often followed by the crescendo of heroic chords. When I was in Vietnam, there was this guy, a South Vietnamese corporal. He'd come around just to visit with some of the guys in my unit. I didn't know him well. I still liked him. We were about the same age, about the same rank. One day, he left on a mission. Maybe a month later, he came back to visit again. I saw him sitting on a bunk. He was missing his left leg. Nobody talked to him. And I mean me too. All I could do was, for a second, just stare. Then I walked away. Except I never really left. Fifty-two years later, all I can do is still stare. That's a leg wound.

Here's another leg wound. In 1975, during the Fall Of Saigon, I was an undergraduate going to Southern Methodist University on my G. I. Bill. On television, a Vietnamese woman and her girl sat on a bench. Both were wounded. Surprisingly, there was little blood. She was shot in the shoulder. The wound was not ragged. It was as if someone neatly scooped out her shoulder. The child's legs were gone. They just sat and waited for medical care. They had no more expression than folks have while waiting for a flu shot.

I don’t understand why the horrors of past wars aren’t enough to stop us from ever fighting again. In 1978, I spent a week on Iona, a little island in Scotland. By then, I was a graduate student researching medieval history. One afternoon, as I passed Iona's war memorial, I counted the names of those local boys who died in World War I. There were 27 names. It occurred to me that, since this fishing village never numbered more than 100 folks, these were the names of virtually all the young men, all of them except the guy who came home without a hand, or the guy who came home half-crazy. I read this line in the post-war letter of an English woman. She said, “We will have to have a new standard for male beauty.” Meaning, don’t complain that your man is missing a leg: you’re lucky you have a man.

Iona has a royal graveyard. MacBeth is said to be buried there. Of all the royal burials, I only remember one grave. It is marked with a simple slab from the Second World War. It reads, “A German sailor known only to God.” I don't understand why this one grave alone isn't enough to halt all future wars.

As I write, it is 3 AM. This is when I feel them most keenly, the boys who died in Vietnam. You would think that such memories would be most appropriate for Memorial Day or Veterans Day. But I’ll not think of Eric any more on those days than I do on any other day. What remains is not romantic. As I age, what remains is a sadness that haunts me just before I sleep. Rob, who never knew the love of a good woman. Hank, who never lived in a house. Pete, who wasn’t there the day his daughter graduated from college. I remember two soldiers, boys really, just 17, who committed suicide in Vietnam. Now, in my old age, after wars and more wars, I despair of – What? – some flaw in the human spirit, some romance of patriotism and death, some murderous impulse that drives us toward war after war after war.