Axar.az presents an article "Rights And Obligations" by John Samuel Tieman.

My grandfather, Sam Wimer, told me of a party he threw during Prohibition. He fondly recalled that Barney Dickman was his bartender. In 1932, Dickman, the Democrat, beat my grandfather, the Republican, in the race for mayor of St. Louis. They remained friends. Today, such civility seems quaint, like an artifact from another era.

Former president Trump is running for reelection. On CNN, he recently did a national town hall. He lied voluminously. He was misogynistic, cruel, racist, and xenophobic. What is more disturbing, however, is the support he got from the audience. For example, in response to tough questioning, Trump called his host, Kaitlan Collins, “a very nasty person.” His supporters in the audience wildly clapped and hooted at all this. I don't fault Trump for being Trump. I fault his followers for abandoning civility.

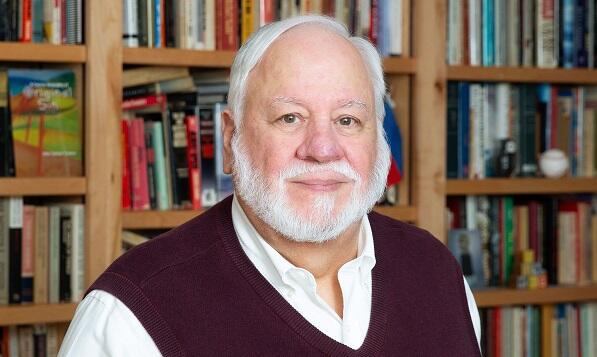

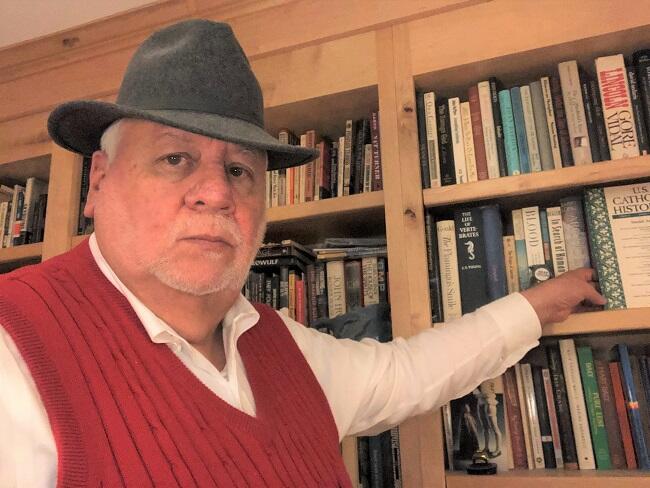

I just finished reading “The Bill Of Obligations: The Ten Habits Of Good Citizens” by Richard Haass. Haass earned his D. Phil. from Oxford. He has held a variety of diplomatic positions, among them Special Envoy To Northern Ireland and President Of The Council On Foreign Relations. The thesis of his new book is that rights by themselves cannot sustain a republic and that rights must be wedded to obligations. As a matter of law, such obligations cannot be mandated. Indeed, these obligations may, or may not, directly benefit the individual, but will over time contribute to the common good. Put it this way. There are rights. There are also obligations. Our founders, for instance, predicated our republic upon an informed electorate. You can legislate someone's right to vote. However, you cannot legislate that someone should be informed. No law can mandate that a citizen should subscribe to a reliable news service.

The book lists ten obligations. They are: 1. Be informed; 2. Get involved; 3. Stay open to compromise; 4. Remain civil; 5. Reject violence; 6. Value norms; 7. Promote the common good; 8. Respect government service; 9. Support the teaching of civics; 10. Put country first. The obligations are not simply niceties. They are necessities.

We live in a time when for many, for far too many, politics means apathy, anger, selfishness, cynicism, division, disinformation, and violence. Because of all that, I think this book is timely. I also think it shocking that we have to be reminded that this is how responsible citizens function. When the former president called his host “a nasty person”, he was cheered. I worry not that we need Dr Haass' book. I worry that we need a reminder that citizens should be civil when engaging in political discourse.

There are 435 representatives, 100 senators, nine justices on the high court, a president and his cabinet. Given those numbers, there has always been a crazy or two in the crowd. Not long after Trump was elected, I saw a white nationalist on TV. He made the point that folks like him “now have a seat at the table.” Marjorie Taylor Greene, a Republican from Georgia, sits in the House of Representatives. She openly espouses the “Great Replacement Theory”, the idea that non-white immigrants are replacing white citizens. Usually, such blatant racism would be tempered, even thwarted, by a system that functions within a clear set of standards. That system still functions, although at times just barely.

A lot of people say we need more religion in public life. Perhaps religion is part of the problem. People who are poorly churched see the world as split into good and evil. The other is always the evil one. But the ten obligations, of which Dr. Haass speaks, force us to consider an eleventh obligation. We must recognize the full humanity of the other. We regard our political opponents not with scorn but with loyal opposition. At a minimum, we must attend to the words of the great poet of Ghana, John Atukwei Okai. “Between me and my God / There are only eleven commandments; / The eleventh says: Thou shalt not / Bury thy brother alive”.

.jpg)