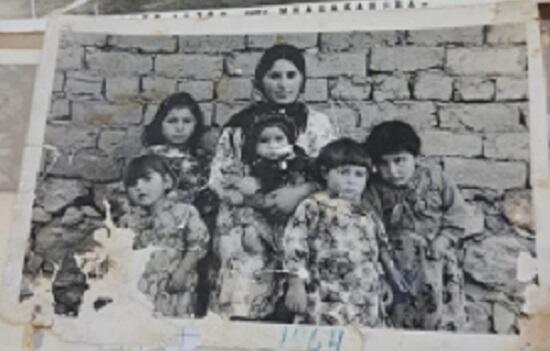

Axar.az presents an article titled 'A Story of Pain' featuring an interview with Elmira Huseynova from Western Azerbaijan.

They beheaded the victims and piled their heads in front of women and children.

“The deportation is etched like a mountain in the memory of our generation” — Elmira Huseynova from Western Azerbaijan speaks about the horrors committed by Armenians.

Western Azerbaijan was once the ancestral homeland of Azerbaijanis, but over time hundreds of thousands of people were forcibly expelled from these lands in various years. Every family carries a story of deportation, massacre, and loss in their memory. One such story belongs to Huseynova Elmira Mammad gizi ’s family and lineage. In this interview, Elmira speaks not only about her own life but also about the genocide, deportation, and fate of their villages that have been etched into the shared memory of generations. What she recounts are truths that do not appear in history books but live on in memories. The four waves of deportation her family endured, the horrific massacre in their village, the struggles of women and children to survive, and the fate of historical monuments — all these are small yet powerful fragments of a nation's pain...

— Please introduce yourself.

— My name is Huseynova Elmira Mammad gizi. I was born in the village of Amagu, in the Keshkand district of the Daralayaz region, Western Azerbaijan (present-day Armenia). During the tragic events of 1987, I, like many of my fellow countrymen, was forcibly deported and took refuge in Azerbaijan. Since then, I have been living in Baku.

— How did the deportation affect your family? And how many times did your family have to endure such trauma?

— Deportation left deep scars on our family as well. My grandfather, Huseynov Ismayil Mammad oglu , spoke to us about the first wave of deportation in 1905, which he remembered from his childhood. According to him, he was about 8 or 9 years old at the time. They were deported from the village of Gishlag in the Keshkand district of Western Azerbaijan. The entire family fled to Iran, where they lived until 1907, before returning to their village.

The second deportation occurred in 1918. My grandmother Asli was around 11 or 12 years old then. Once again, they had to leave the village and relocated to the Shahbuz region of Nakhchivan. After living there for a while, they returned home.

The third deportation took place in 1948. At that time, my father was between 10 and 18 years old and remembered the events vividly. That time, they were deported from Gishlag village to the Salyan district. However, due to the unsuitable climate, my family moved to the Babak region of Nakhchivan. My grandmother’s brothers and cousins had already relocated to Babak during the 1905 and 1918 deportations and were living there. So my grandparents, father, and uncles joined them.

But they didn’t stay there long — after some time, they moved back to the village of Amagu. My grandfather passed away in that village in 1977, and my grandmother in 1982.

– What do you know about the genocide that took place in your village in 1918?

– Based on my mother's stories and her mother's memories, I can say that a real genocide took place in our village in 1918. It can be said that no one who held a rifle in their hands and was able to work survived. My great-grandmother witnessed the terrible events of 1918 with her own eyes. She said that at that time, people from neighboring villages were also hiding in our village. Trenches were dug, and people hid there. But even that didn't help—they found everyone and took them away. According to my grandmother, the women and children were gathered in a dark and stuffy place without windows, called the “black roof,” on the outskirts of the village. The men, boys, and all young people were separated one by one, their weapons were taken away, and they were all shot. The most horrific thing was that they cut off the heads of those killed and gathered them in front of the women and children. The goal was clear: to sow fear and break their will. They committed these atrocities in front of women, mothers, sisters, and spouses. Then they set fire to the bodies. They did not even spare the crying children. My mother said that they pierced crying babies with spears, and some were thrown into the fire alive and burned. The few surviving men were chained, taken to the mountains, and shot there. My mother said that her aunt's husband was in this group. When it was his turn, he tried to kill himself by throwing himself off a cliff before the shots rang out. When darkness fell, the killers retreated. He, wounded, crawled to the village of Jaghazir in the Sharur region of Nakhchivan. There he learned about the surviving women and children, and then, with great difficulty, found her wife, my mother's aunt. In our family, we said, “No eye should see, no tongue should speak of what they went through.” That's how they talked about those years...

— But it seems the tragedy left such a deep imprint on people's blood memory that every detail has been passed down to you and the next generations…

— Yes, exactly. We would gather around the elderly women in our village — those who had witnessed the horrors with their own eyes — and listen to their accounts of the tragedy. They used to say that the 1918 massacre was the most painful of all the disasters they had endured.

To prevent an attack by Armenian Dashnak militants, the village had been surrounded with defensive trenches on all four sides: the main trench, the middle trench, a place called “the fortress,” and the hills known as “where outlaws were hunted.” All these were used for defense.

There was a story they used to tell: an Armenian fighter once shouted to the villagers, “Surrender — your son is in my hands, I will let him go.” Believing him, the father surrendered. But shortly after, they beheaded his son right in the center of the village and killed all those who had surrendered.

It is said that only two people survived that massacre: one woman and one man. The woman — who was my uncle’s mother-in-law — told us she had been stabbed with a bayonet. The Armenians were checking the bodies to make sure no one had survived, stabbing them with bayonets. When the bayonet pierced her leg, she held her breath and stayed completely still. After the attackers left, she crawled to a nearby village. Her leg was infected, and she was cared for several days. The bayonet scar remained with her for the rest of her life.

There was also an old woman named Javahir — her head always trembled. It was said that Armenians had slashed her head with a dagger. She had survived, but her head had constantly shaken ever since. We saw her with our own eyes.

Despite all these horrors, the villagers never wanted to leave their land — their stones, their springs, their graves, and the homes they had built with their own hands. “They killed us, burned us, but they couldn’t erase our memory,” they used to say. And they returned to live on that land once again...

— There were many historical monuments in your village. But perhaps the most fascinating was the Albanian temple and its sorrowful history. What do you remember about it?

— About two or three kilometers from our village, there was a very interesting and mysterious Albanian temple. We used to call it “Lang,” but after we were displaced, they started referring to it as “Noravank.” The interior of the temple was extremely tall — it had two floors. There was a narrow and dangerous stone staircase outside that led to the second floor. But even from the first floor, you could see the ceiling of the second level — that’s how high it was.

The walls of the temple were covered with inscriptions and drawings that we couldn’t recognize. The letters weren’t Arabic, nor did they resemble the Armenian alphabet. When we asked about them, people told us they belonged to the ancient Albanians. There was a depiction of a family — a man, a woman, and a child — a full family composition carved into the wall.

I clearly remember that when I was around 14 or 15, a helicopter once came to the village. They said there was a very valuable and important stone inside the temple. That helicopter took the stone away. At the time, people were saying that it had been taken to France. The event caused great surprise in the village.

Some believed that the second floor of the temple was built so that men and women could be separated during worship — so they wouldn’t see each other. The stairs were so narrow and steep that it was terrifying to climb. In our village, that temple was treated with great respect and protected. Even later on, when we were still living there, people from the “other side” — the current occupiers — would ask permission from our villagers to sit there, eat, drink, and have fun. The locals never allowed it.

Now, that entire place has been completely transformed, rebuilt from the ground up, and turned into a tourist zone. That land, that village — it was unforgettable. We had healing springs, towering mountains, and medicinal herbs that grew in the highlands. Every stone, every tree, every hill held memories. The graves of our loved ones, the souls of our ancestors, remained there. And now… they’ve erased all traces of us. Our cemeteries have been destroyed, leveled to the ground.

These events are etched into the memory of an entire generation. And we have no right to forget this pain.