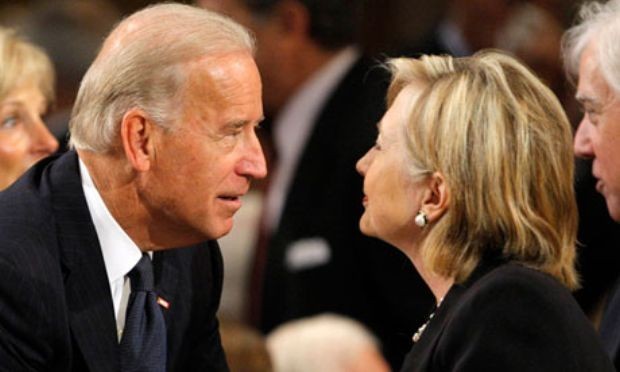

Joe Biden is at the top of the internal short list

Hillary Clinton’s transition team is preparing for her pick to be

secretary of state, reported political news agency

Politico.

This would be the first major Cabinet candidate to go public for

a campaign that’s insisted its focus remains on winning the

election, and perhaps the most central choice for a potential

president who was a secretary of state herself.

Neither Clinton, nor her aides have yet told Biden. According to

the source, they’re strategizing about how to make the approach to

the vice president, who almost ran against her in the Democratic

primaries but has since been campaigning for her at a breakneck

pace all over the country in these final months.

"He'd be great, and they are spending a lot of time figuring out

the best way to try to persuade him to do it if she wins," said the

source familiar with the transition planning.

The vice president, who chaired the Senate Foreign Relations

Committee before joining the administration, is one of the most

experienced and respected Democrats on the world stage. He’s also

coming to what would be the close of a 44-year career in

Washington, first with six terms in the Senate and then two terms

as President Barack Obama’s closest adviser — and the keeper of the

portfolio on some of the most difficult international issues,

including Iraq and Ukraine.

Those will carry over to the next administration, as will a

concern within Clinton’s circle and throughout the current White

House that Donald Trump’s campaign has created lasting damage to

America’s relationships around the world.

Biden’s already been deployed to mitigate that damage by Obama.

In August, he traveled to Latvia to assure NATO allies that

America’s commitment to them will hold, despite Trump’s questioning

of the alliance’s value and worries especially within the Baltic

region about Russian aggression.

Just on Monday, on a stop at a Clinton campaign office in

Toledo, Biden said that he’d spoken to the Latvian president, who’d

urged him to come to Europe and reassure people that if Russia

invades, NATO will defend them.

At that same stop, Biden said he’d hoped to continue some level

of involvement in domestic and foreign policy, but added, "I may

write a book. This might disappoint you, it won’t be a tell-all

book."

Clinton and Biden have a long history together, going back to

her days as first lady. They both lost to Obama in the 2008

primaries and went on to serve together in his administration — and

though they had regular lunches and a warm personal relationship,

feelings became rougher as her 2016 run came into focus and the

chances of his running again faded.

Biden bristled at being portrayed as a holdout in greenlighting

the raid that killed Osama bin Laden while Clinton was a seen as a

strong advocate, and the day before he pulled the plug on running,

publicly corrected the record to say he’d privately advised Obama

to go ahead with it.

In Biden, Clinton would be tapping a seasoned hand on foreign

policy, a glad-handing pol with a long memory and a well of deep

relationships around the globe.

But she’d also be choosing someone with whom she repeatedly

clashed as secretary of state, with the vice president often

playing the skeptic while she supported more aggressive action.

They differed over leaving troops in Iraq, the surge in

Afghanistan, and whether to arm Syria’s rebels and bomb Libya — and

Clinton took the more hawkish line in every case. During the Obama

administration’s lengthy review of Afghanistan policy early in his

tenure, for instance, a skeptical Biden urged the president not to

escalate the war, while Clinton backed Gen. Stanley McChrystal’s

request for 40,000 more troops.

Clinton’s campaign was anxious about Biden running — and was

watching carefully enough to be gaming out whether he’d announce in

an appearance on the "Late Show with Stephen Colbert" last

September, as shown in emails revealed by the WikiLeaks hack.

The speculation over who Clinton might pick to fill a job she

once held is a confounding one for Washington’s tight-knit foreign

policy community. Will she select a politician in her own mold, or

a career diplomat more in line with Foggy Bottom tradition?

Among the names most discussed: former undersecretary of state

Wendy Sherman, the point person on the Iran deal and a favorite

within the State Department; former Deputy Secretary of State Bill

Burns, who now heads the Carnegie Endowment for International

Peace; Nick Burns, the former under secretary of state of political

affairs under George W. Bush who’s been an active advocate for

Clinton this year; Kurt Campbell, Clinton’s assistant secretary of

state for East Asian and Pacific Affairs when she was in the job;

Strobe Talbott, the deputy secretary of state during Bill Clinton’s

first term and a longtime friend of the Clintons who’s now the

president of the Brookings Institution; and James Stavridis, the

retired admiral who earlier this summer made it into consideration

as the sleeper pick to be her running mate.

But none of those picks would come with the star power that's

been a feature for all recent picks for the job, and which Biden

would bring in buckets.

The Clinton campaign did not respond to several requests for

comment.